26 Mar Sam French, 2023 Free Speech Film Festival Official Selection Winner, Believes in Amplifying the Voices of Others

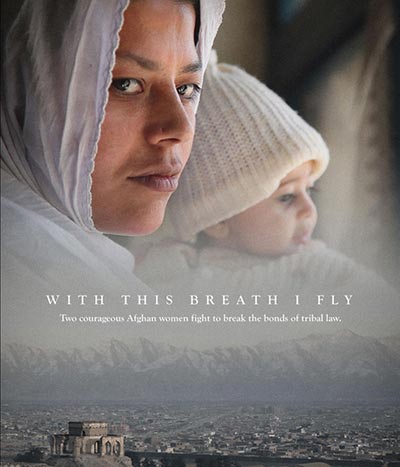

Freedom of Speech isn’t just about having the ability to physically speak out; it’s about having the right to speak out and being able to express your thoughts in a public forum. Sam French saw this first-hand when he served as co-director of With This Breath I Fly, which was named an Official Selection winning-film in the 2023 Free Speech Film Festival.

Sam French, Director

Sam and co-director Clementine Malpas began making the film at the height of the international occupation of Afghanistan. It follows the story of Gulnaz, who was raped and impregnated by her uncle, and Farida, who is on the run from an abusive husband. The film’s synopsis says both women “were imprisoned on charges of ‘moral crimes’ by an Afghan justice system that is supported by billions of dollars of aid money from the European Union. Shot over ten years, With This Breath I Fly follows these two courageous women as they fight for their freedom against a patriarchal Afghan society determined to keep them bound to tribal culture, while exposing the complicity of the European Union in censoring their voices, and how the international press – and our documentary – forever alters the course of their lives.”

With This Breath I Fly has won a dozen awards at festivals around the world, including the Grand Prize at the 2023 Women’s Voices Film Festival, Best International Documentary at the 2022 Evolution Mallorca International Film Festival, Best Documentary at the San Diego International Film Festival, Best Character Driven Documentary at the 2022 Lonely Wolf International Film Festival, Best Feature Documentary at the Berlin Film Haus, and Best of Show at the 2021 Docs Without Borders Film Festival, and the Audience Award at the Austin Film Festival, which was the first award the film won. It was also named an Official Selection at 10 festivals.

Sam said creating the film taught him a lot about the true meaning behind democracy and freedom of speech. “We like to spread the idea of democracy as a paragon of American exceptionalism. But democracy doesn’t work without the rule of law and freedom of speech and freedom of the press. The theme of this film is that these women had only one power, which was their voice. They could speak. They weren’t silenced. We were allowed in to film with them and the news media, once they got a hold of the story, were allowed to interview Gulnaz, so her story was disseminated across the world. But democracy and freedom only works if people’s speech is respected and they are allowed to speak,” he said.

He added, “In this age today of disinformation, demagoguery and the proliferation of narratives that are taking over people’s brains, it’s like this psychological virus that’s happening across the world and it’s not new. It’s been happening since the beginning of the time. A lot of people seem to think that the repression of speech is the worst thing that could possibly happen, but I think it depends on who you listen to. If you are forced to listen to people who spread a false narrative, that is almost worse. So my goal has always been to amplify the voices of those who are not able to participate in that narrative.

People aren’t silenced because you can’t silence people but you can overwhelm them and drown them out. So democracy only works when there’s free accessing information and you can have an actual discussion in the public square. In a place like Afghanistan, women are silenced and don’t get to speak.”

Sam said there are many places around the world, including Afghanistan, where people feel they have to conform what they say to match the narrative of those who are in power. Although Afghanistan worked to create a free press in the early 2000s, now that the Taliban is in charge they are focusing on silencing anyone who doesn’t fit with their narrative.

“For me, free speech is protecting not just the right to speak, but protecting those who are vulnerable when they raise their voices. In Afghanistan, the Taliban controls the media and they control access to education, which is also about free speech. So women aren’t allowed to go to school and that’s a deliberate thing to silence different thoughts, so they can only understand and parrot the narrative of the male oppressor,” he added.

Sam said it was frustrating for him as a filmmaker to watch the oppression that was happening to Gulnaz and Farida because the storyteller in him wanted these women to have the right to share their story.

Sam said it was frustrating for him as a filmmaker to watch the oppression that was happening to Gulnaz and Farida because the storyteller in him wanted these women to have the right to share their story.

“I’m not an activist, per se, I don’t make films as activism pieces; I make films as stories. But I guess I would say I’m an activist for storytelling because I think the most powerful thing you can do is to tell a story with honor and integrity and ethics and understand how you might be able to tell a narrative that’s compelling and different,” he said. “I think the reason why the stories of Gulnaz and Farida are so powerful is that we were able to let them tell their stories and give them the time and space to do that. It’s about allowing them the freedom and security to speak their own stories.”

Speaking of personal stories, Sam has his own interesting path to how he ended up in Afghanistan to create this film. He attended Williams College as an English major and worked in New York City on television and independent film production projects before heading to the University of Southern California in 2002 for graduate school. When he graduated in 2007, he thought he would follow a path to be the next big narrative film director like Steven Spielberg but fate had other plans for him.

“ I met and fell in love with this beautiful British diplomat who ended up getting posted to Kabul, Afghanistan, and I decided to pick everything up and leave and go visit her and ended up staying for five years. The country of Afghanistan was, and still is in many ways, incredible and full of wonderful, generous, funny Afghans. And I didn’t see the country that I was experiencing on the news. So I set out to create a documentary production company called Development Pictures, which aimed to tell stories behind the headlines that weren’t being reported. I produced a lot of pieces for the news organizations like CNN and BBC and then our company also focused on doing documentaries for the UN and other NGOs. That was a good way of staying in business because there was a lot of money being poured into the country,” he said.

His first independent project in Afghanistan was a narrative short film called Buzkashi Boys, which told the story of two young boys coming of age in a war-torn city. The film went on to be nominated for an Academy Award and was a big hit with the Afghan people. Sam said that one of his favorite things about creating Buzkashi Boys and With This Breath I Fly was being able to amplify the voices of others.

“The goal is to amplify the voices of those who might not be able to be heard. I’m not telling their story or giving them a voice because they already have voices, but I’m amplifying their voices and being that conduit across cultures,” he said. “I think the best part about filmmaking is immersing yourself in another culture, understanding other perspectives and having empathy for other people. And I am just so blessed to be able to do this work because it’s made me grow as a person. It’s humbled me. You know, I went to Afghanistan as sort of an arrogant white guy and I left the country as an ally. I really want to be part of the conversation we’re all having in America and across the world about lifting up underrepresented voices and marginalized stories and really respecting storytellers. I think I hope to better understand my white privilege as well, which is a lifelong pursuit. I definitely better understand it now, having done the documentary work that I’ve done, and realizing, in many ways, I am certainly not the center of the story. So I think that has been a good growth for me, and I think it’s something that I would like to spread and share to other filmmakers.”

Sam said the decision to amplify the voices of Gulnaz and Farida through With This Breath I Fly began through his friendship with two women, Co-Director Malpas and Producer Leslie Knott. The three filmmakers had been looking for a chance to tell stories about women in Afghanistan for a while when they discovered that the European Union had offered a contract to filmmakers to talk about women’s rights, so they pitched the idea of a film about women in prison for moral crimes. Although it took many meetings with the Minister of Justice in Afghanistan, they eventually were granted unfettered access to the prisons.

Ultimately, Sam said the theme of the film was to tell the story of these women through their own eyes. “The genesis of the film was really trying to promote empathy for other people and communication across cultures. The judges who were ruling on these cases did not follow the constitutional law that was written in the Constitution in many ways. They really were still beholden to tribal law in sentencing these women and I think that, for us, the theme of the documentary first and foremost was just understanding who these women were and what they were going through. That’s the guiding light we were following,” he said.

Sam said that because of many obstacles they faced with the European Union, it took about 10 years to complete the film. They followed the women actively for three years and filmed what became the major arc of their story but they went back and checked on them periodically over the next seven years. They completed their final filming in 2018. While the money they received from the EU contract helped, it didn’t fund the entire project so they spent many years raising enough money to finish the film.

“We did many crowdfunding campaigns and just managed to get enough money. We would hire an editor and then run out of money and then have to do another fundraising push and then hire another editor and then run out of money. And then repeat and repeat so that’s why it took so long to finish the film. But also, we didn’t want to finish the film before we understood exactly how everything played out at the end,” he said. “It’s unusual in filmmaking that you have that amount of time to craft the story. Once the fight with the European Union was done, we realized we were not even halfway done and we had to keep on filming what was happening next. We could have interviewed people later and used archival footage but we wanted to actually be there and interview and hang out with Gulnaz and her lawyer, Kim, in the shelter as she was trying to get asylum, so that’s why it took so long”

Prior to the Taliban taking control of the country, Sam said there were many examples of people expressing their right to free speech in Afghanistan, everything from rock and roll bands speaking out in song to national new stories that were broadcast across the country. He said he also learned about an underground poetry group of Afghan women who used poems to express their thoughts.

“You cannot repress speech, you can only punish it. So, it will always bubble up and I think the natural tendency of human beings is to seek connection and humanity and laughter and poetry and beauty. When you try to repress that speech and other perspectives, that’s when conflict happens,” he said.

Since the theme of the film was amplifying the voices of these imprisoned women, Sam said it made perfect sense to submit it to the Free Speech Film Festival. “The mission of this festival is really important. Also, one personal reason for me to submit there is that I grew up in Philadelphia. The festival has connections with the incredible history of Philadelphia as well, which is the bastion of speech here in America, being where the Constitution was drafted,” he said. “Making this film between Afghanistan and America, there’s connections between the themes of this film and the themes of what’s happening in America right now in terms of repressing and trying to control the narrative. And so, being in Philadelphia, with that connection to the founding of this country, and how free speech was prioritized, rightly so, and understood to be the thing that would make this country great, I think has some power there.”

Sam encourages other filmmakers to continue making films that will be part of a larger conversation and consider entering them in the Free Speech Film Festival. “The fact that our job was to amplify these women’s voices didn’t occur to me until the last couple months of editing. So I would tell other filmmakers to take the time to stick with the film and understand what the footage is trying to tell you is. Through making this film, I also learned that imposing my own narrative on it didn’t make it better. So, I think having it reveal its narrative to you, as a film and a story, is important.”

No Comments