07 Feb Interview with Vida Lercari, Director of Means of Expression

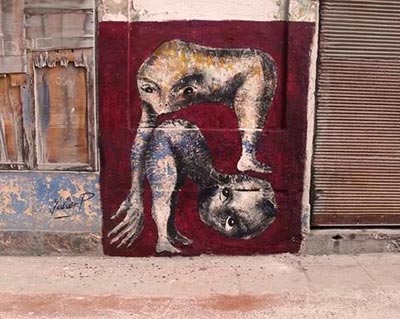

Means of Expression (2020) is a film that explores illegal public art in Cuba through the eyes of street artist Yulier P. The documentary shows how despite restrictive rules, Yulier P. does all that he can to portray his Cuban reality through murals on abandoned or dilapidated structures across the city, hoping to inspire conversation and change in his country.

—

Free Speech Film Festival: Tell us about yourself. How has making your film impacted who you are today?

Vida Lecari, Director of Means of Expression

FSFF: Why did you choose to show this topic? What made it stand out to you? Why do you think it will stand out to others?

VL: Growing up in NYC I developed a fascination with street art, graffiti, and other forms of public art. For me, it’s one of the beautiful things about living in an urban place. It can function as a form of democracy, allowing anyone to be a part of the public sphere and express themselves within their own community. When I was studying in Cuba I was immediately taken by the various forms of street art I saw, and after getting to know a handful of Havana’s street artists and really involving myself in their world, I knew I wanted to create something that allowed space for Cuban artists to tell their stories, as well as explain what it means to be a Cuban street artist living and working in a space that is so vibrant with life yet is also under the umbrella of a repressive government. Part of what made this community stand out to me, and why I think it will stand out to other people, is these artists’ resilience and resourcefulness. Given the cards they are dealt, they know how to make the most out of their situation and are able to create beautiful things despite the hurdles they face on a daily basis.

FSFF: You made this film for a reason. What kind of change do you think it will bring about?

VL: I believe spreading information and ideas can produce a slow burning change that doesn’t necessarily show itself overnight. I’m hoping this film can be informative to people who don’t know much about what life is really like for Cuban street artists/citizens in general. A lot of media representation of Cuba is tainted with opinions from our countries’ past and ongoing differences and rarely do we get to hear directly from citizens themselves. This film is not only about public forms of expression, but is also about what living in modern day Havana is like, and I hope that watching my film can realign some people’s perceptions.

FSFF: In terms of restrictions on art, what steps do you think are necessary to stop it from happening?

VL: I think that there needs to be a sense of mutual understanding between local officials and the artists. A city is public space, but of course there are boundaries that artists need to respect. I am of the belief that public art and graffiti enhance a city, and I could imagine a way for there to be designated spaces in public places that encourage expression. Of course, that would also require a form of government that allows for complete freedom of expression, which Cuba does not have in this current moment. I’m not sure what the steps would be to make a government allow freedom of expression, other than peaceful protesting and expressed civil unrest. Cultural change begins at the grassroots.

VL: I think that there needs to be a sense of mutual understanding between local officials and the artists. A city is public space, but of course there are boundaries that artists need to respect. I am of the belief that public art and graffiti enhance a city, and I could imagine a way for there to be designated spaces in public places that encourage expression. Of course, that would also require a form of government that allows for complete freedom of expression, which Cuba does not have in this current moment. I’m not sure what the steps would be to make a government allow freedom of expression, other than peaceful protesting and expressed civil unrest. Cultural change begins at the grassroots.

FSFF: How can those who may not have free speech make a difference in their communities?

VL: I’ve seen firsthand by making this film how people without access to free speech can make a difference in their communities. Sometimes in order to get ideas across, you have to be bold and do what you feel is right. For Yulier, that meant creating murals for his community to enjoy and relate to. Many people felt that Yulier’s murals represented them in ways that they had not typically been represented. Citizens walking past him while he worked would stop and watch, oftentimes conversing with him and expressing their approval of what he does. Of course, not everyone feels that way.

FSFF: What would you say to a person who disagrees with the stance you are trying to take?

VL: Personally, I was trying not to take too much of a stance with this film, because there are some very legitimate and real counter arguments towards illegal graffiti/unofficial public art. If someone were to vehemently disagree with street art’s right to exist, I would probably try to find a middle ground with that person, discussing the ways that murals and graffiti can visually enhance a city, can allow space for artist citizens to express themselves and their community, and their ability to share creative ideas and culture.

FSFF: Did you always want to go into filmmaking?

VL: Not really, actually. I was in Cuba studying photography, and that’s what I have a degree in. But when I met Yulier and started spending time with him it was like this lightbulb moment that went off in my head where I was thinking, ok, this needs to be documented with a moving image rather than a still one, and it needs to be paired with him telling his story. It just made sense to me in that moment that a film needed to be made.

FSFF: What advice would you give to your past self and to the younger generation about finding your freedom to speak?

VL: Honestly, I’ve never really had to “find” the freedom to speak because I’ve lived in a country that gave it to me upon birth. I guess if I were to give advice to my younger self I might say not to take it for granted, and explain that not everyone has the privilege of free speech, and what that means and looks like.

FSFF: Do you have any other projects you are working on? / What do you see in your future?

VL: Lately I’ve been returning to still photography and shooting some landscapes in upstate New York during quarantine. I don’t have any serious filmmaking projects in the works at the moment, but I’m always watching how the story continues to play out for Yulier and other Cuban street artists/Cuban society in general, so I’m always ready at a moment’s notice to continue filming the process.

FSFF: How important is it that everyone has the power of free speech?

VL: In my opinion, having free speech means having freedom of thought as well, and those two things are so important. By having the freedom of speech and by being surrounded by others with the same privilege, ideas can be shared, opinions can be more greatly informed/developed, and insights can be gained. The power that free speech has reaches well beyond the bounds of the individual, and can really empower entire communities.

Film Summary

Director: Vida Lercari

Cast: Vida Lercari, Jeffry Valadez, Hunter Williams, Rachel Hettleman, and Kyle Jacobson.

Writer: N/A

Vida: Vida Lercari

Year of Production: 2020

Runtime: 20 minutes 25 seconds

Language: Spanish

—

Chynna, 2021 American INSIGHT Intern, Temple University 2021

No Comments